In this chapter

- the definitions of basic derivatives instruments

- option jargon

- how to draw payoff diagrams

- no arbitrage and put-call parity

- simple option strategies

Options

The simplest option gives the holder the right to trade in the future at a previously agreed price but takes away the obligation.

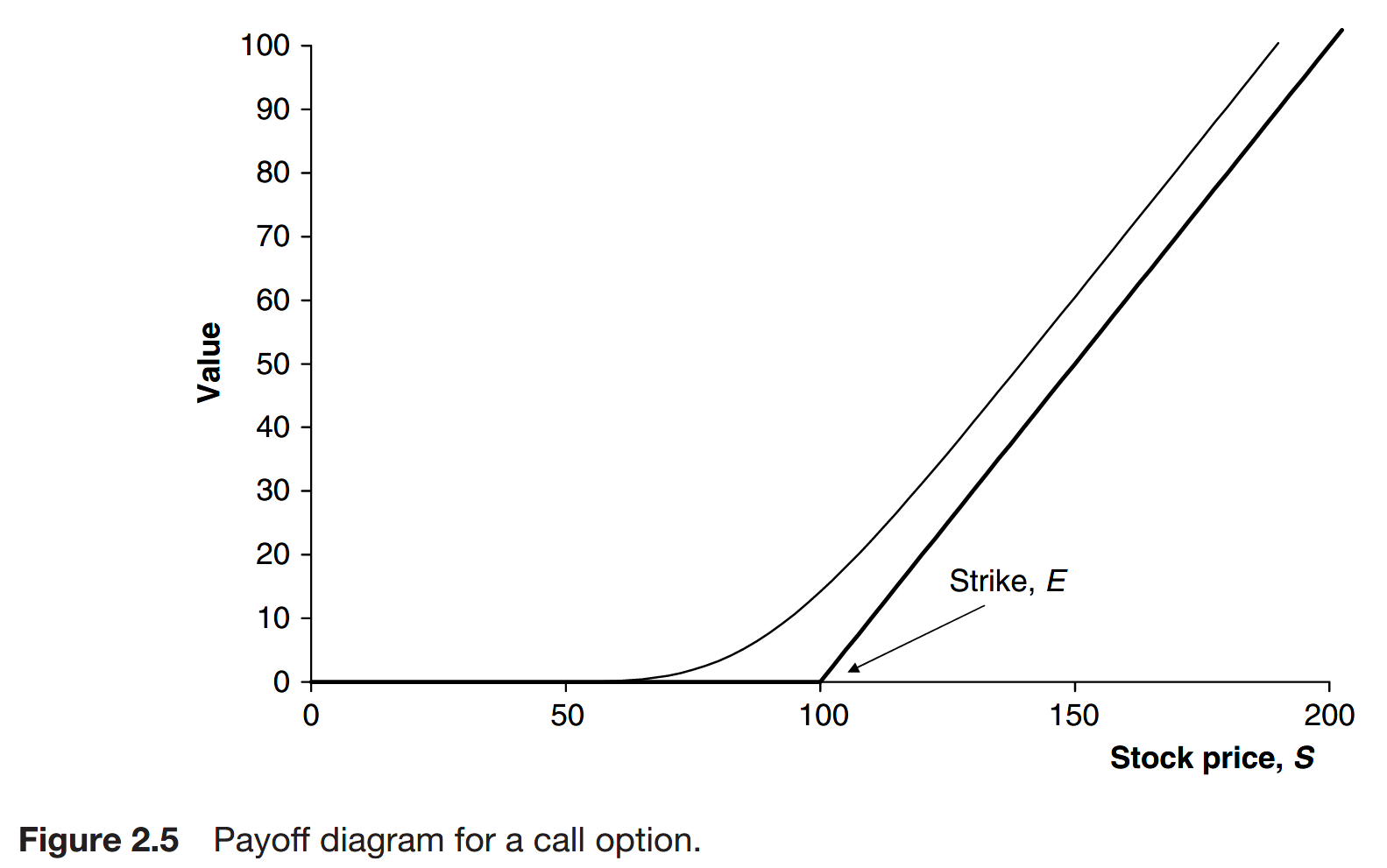

A call option is the right to buy a particular asset for an agreed amount at a specified time in the future.

We can pay for the stock is called the exercise price or strike price. The date on which we must exercise our option, if we decide to, is called the expiry or expiration date. The stock on which the option is based is known as the underlying asset.

payoff function for call option:

A put option is the right to sell a particular asset for an agreed amount at a specified time in the future

As there is less and less time for the underlying to move, so the option value must converge to the payoff function.

calls and puts have a non-linear dependence on the underlying asset. This non-linearity is very important in the pricing of options since the randomness in the underlying asset and the curvature of the option value with respect to the asset are intimately related.

Calls and puts are often referred to as vanilla because of the ubiquity of that flavor. Other terms used to describe contracts with some dependences on a more fundamental asset are derivatives or contingent claims.

Definition of common terms

Underlying (asset)

The financial instrument on which the option value depends. The option payoff is defined as some function of the underlying asset at expiry.

Strike (price) or exercise price

The amount for which the underlying can be bought (call) or sold (put)

Expiration (date) or expiry (date)

Date on which the option can be exercised or date on which the option ceases to exist or give the holder any rights.

Intrinsic value

The payoff that would be received if the underlying is at its current level when the option expires

Time value

The uncertainty surrounding the future value of the underlying asset

In the money

An option with positive intrinsic value

Out of the money

An option who no intrinsic value, only time value

At the money

A call or put with a strike that is close to the current asset level

Long position

A positive amount of a quantity, or a positive exposure to a quantity

Short position

A negative amount of a quantity, or a negative exposure to a quantity

Payoff diagrams

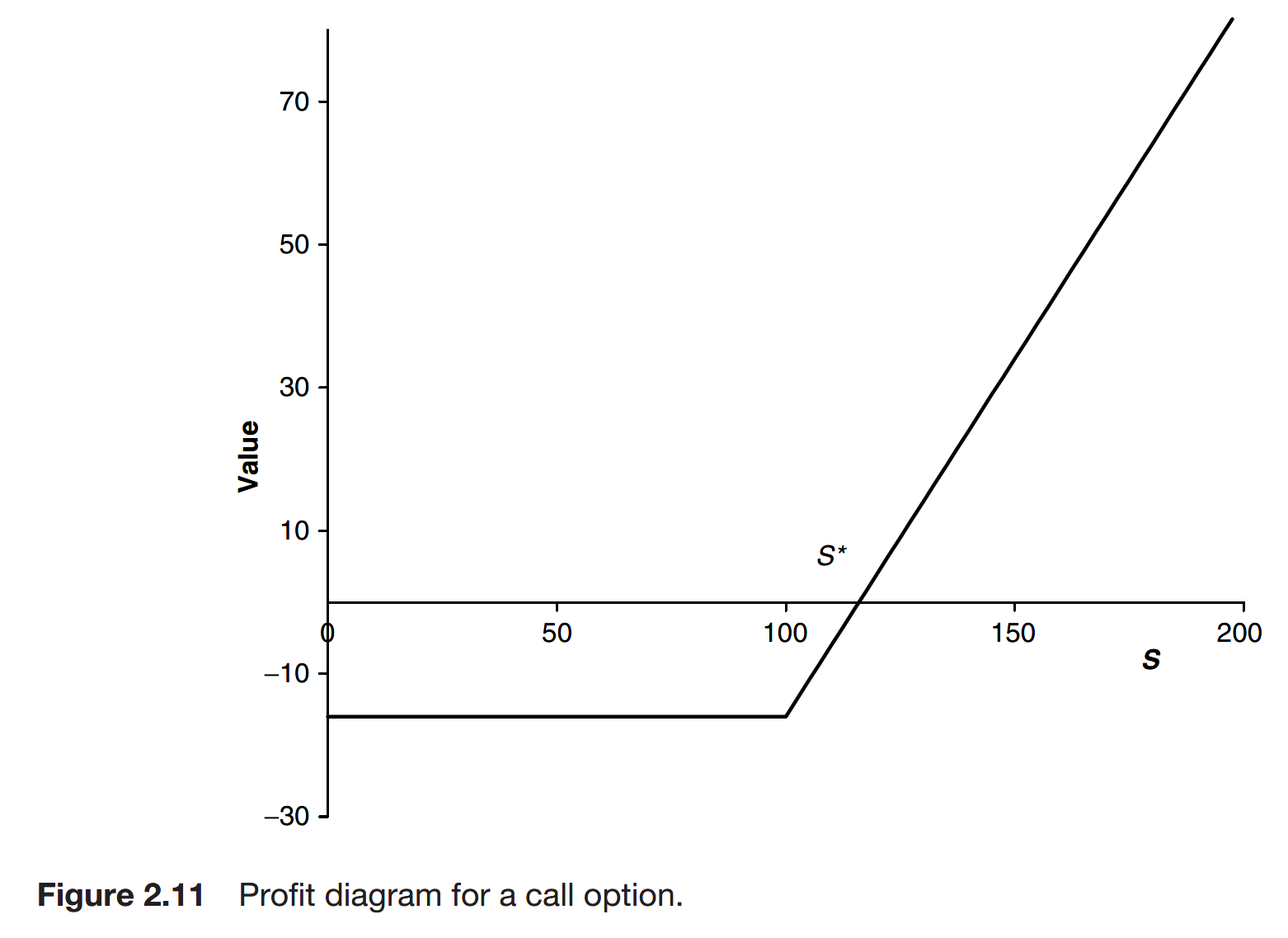

In this profit diagram for a call option I have subtracted from the payoff the premium originally paid for the call option.

Writing options

The writer of an option is the person who promises to deliver the underlying asset, if the option is a call, or buy it, if the option is a put. The writer is the person who receives the premium.

The purchaser of the option bands over a premium in return for special rights, and an uncertain outcome. The writer receives a guaranteed payment up front, but then has obligations in the future.

Margin

To cover the risk of default in the event of an unfavorable outcome, the clearing houses that register and settle options insist on the deposit of a margin by the writers of options. Clearing houses act as counterparty to each transaction.

The initial margin is the amount deposited at the initiation of the contract. The total amount held as margin must stay above a prescribed maintenance margin. When the deposit goes down below the maintenance margin, the deposit should be covered up to the level of initial margin.

Market conventions

Vanilla calls and puts come in series. This refers to the strike and expiry dates.

These agreements can be very flexible and the contract details do not need to satisfy any conventions. Such contracts are known as over the counter or OTC contracts.

The value of the option before expiry

Two things are clear about the contract value before expiry: the value will depend on how high the asset price is today and how long there is before expiry.

The longer the time to expiry, the more time there is for the asset to rise or fall. Is that good or bad if we own a call option? Furthermore, the longer we have to wait until we get any payoff, the less valuable will be that payoff simply because of the time value of money.

Factors affecting derivatives prices

variables - inevitably change during the life of the contract

- underlying asset

- time to expiry

parameters - affect the price of options

- strike price

- interest rate

- dividend

- volatility - measure of the amount of fluctuation in the asset price, a measure of the randomness

The distinction between parameters and variables is very important.

Speculation and gearing

Gearing = leverage

The out-of-the-money option has a high gearing, a possible high payoff for a small investment. The downside of this leverage is that the call option is more likely than not to expire completely worthless and you will lose all of your investment.

Highly-leveraged contracts are very risky for the writer of the option. The buyer is only risking a small amount; although he is very likely to lose, his downside is limited to his initial premium. But the writer is risking a large loss in order to make a probable small profit. The writer is likely to think twice about such a deal unless he can offset his risk by buying other contracts. This offsetting of risk by buying other related contracts is called hedging.

Gearing explains one of the reasons for buying options. If you have a strong view about the direction of the market then you can exploit derivatives to make a better return, if you are right, than buying or selling the underlying.

Early exercise

European options are only permitted to exercise at expiry

American options are allowed to exercise at any time before expiry

Bermudan options are allowed to exercise on specified dates, or in specified periods. In a sense they are half way between European and American since exercise is allowed on some days and not on others.

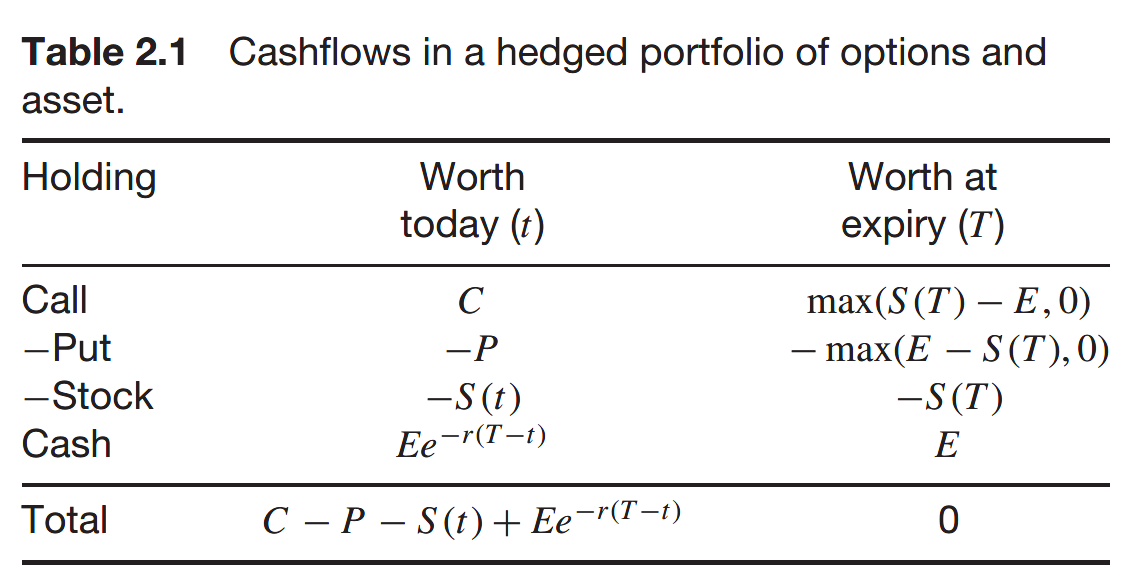

Put-call parity

The conclusion is that the portfolio of a long call and a short put gives me exactly the same payoff as a long asset, short cash position.

Put-call parity - If this relationship did not hold then there would be riskless arbitrage opportunities.

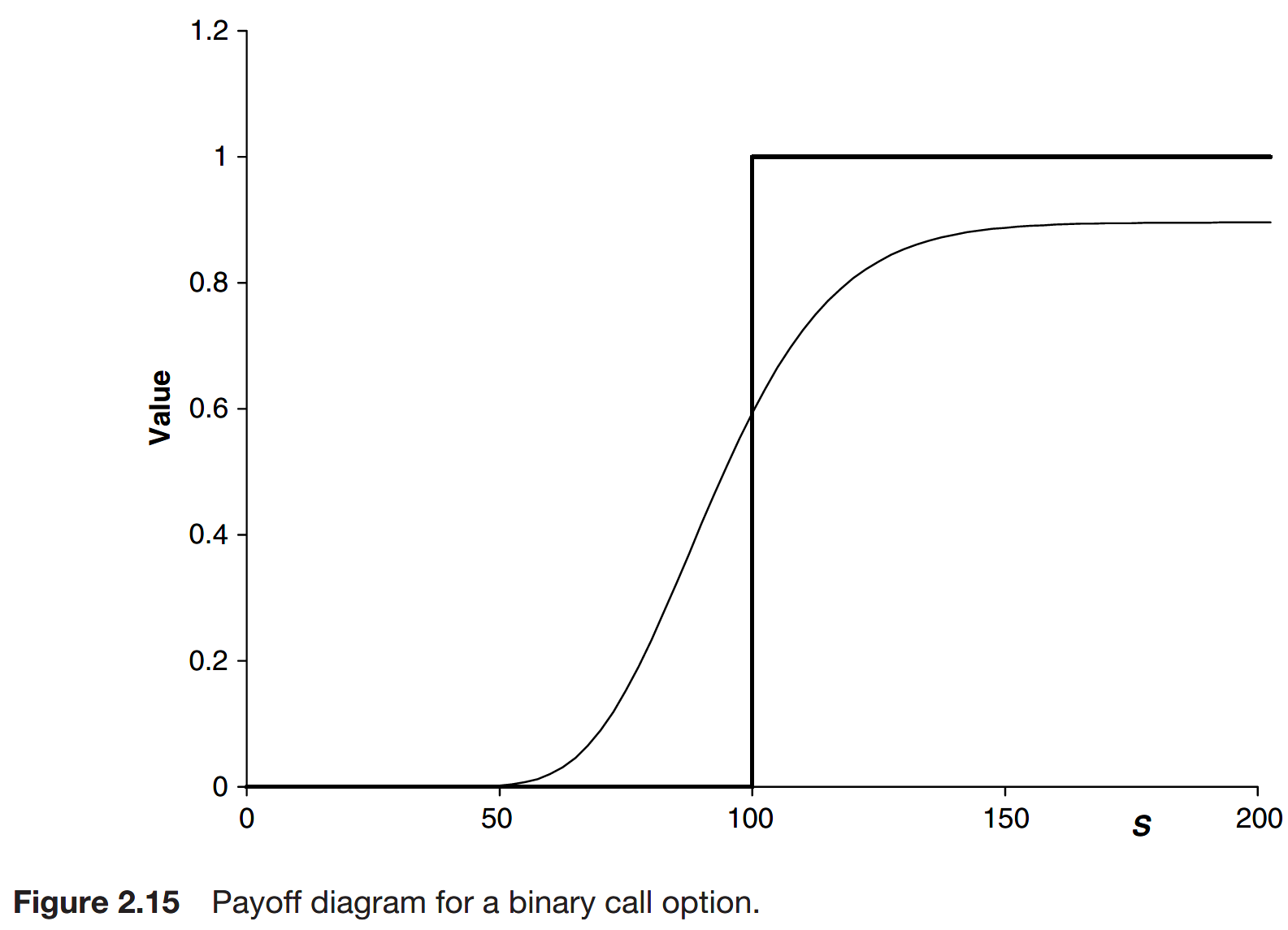

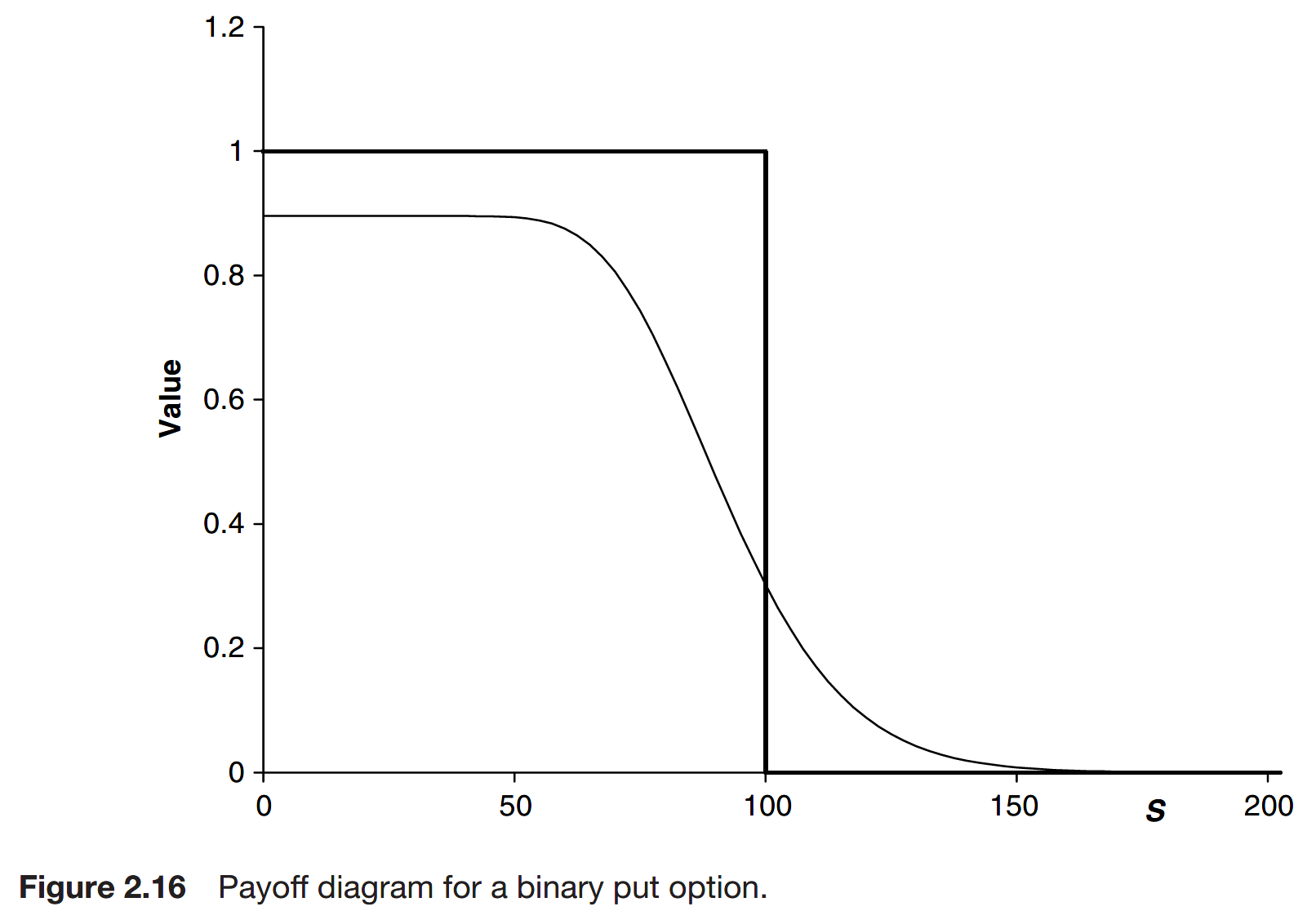

Binaries or digitals

Binary or digital options have a payoff at expiry that is discontinuous in the underlying asset price.

Why would you invest in a binary call? If you think that the asset price will rise by expiry, to finish above the strike price then you might choose to buy either a vanilla call or a binary call. The vanilla call ahs the best upside potential, growing linearly with S beyond the strike. The binary call, however, can never pay off more than the $1. If you expect believe that the asset rise will be less dramatic then buy the binary call. The gearing of the vanilla call is greater than that for a binary call if the move in the underlying is large.

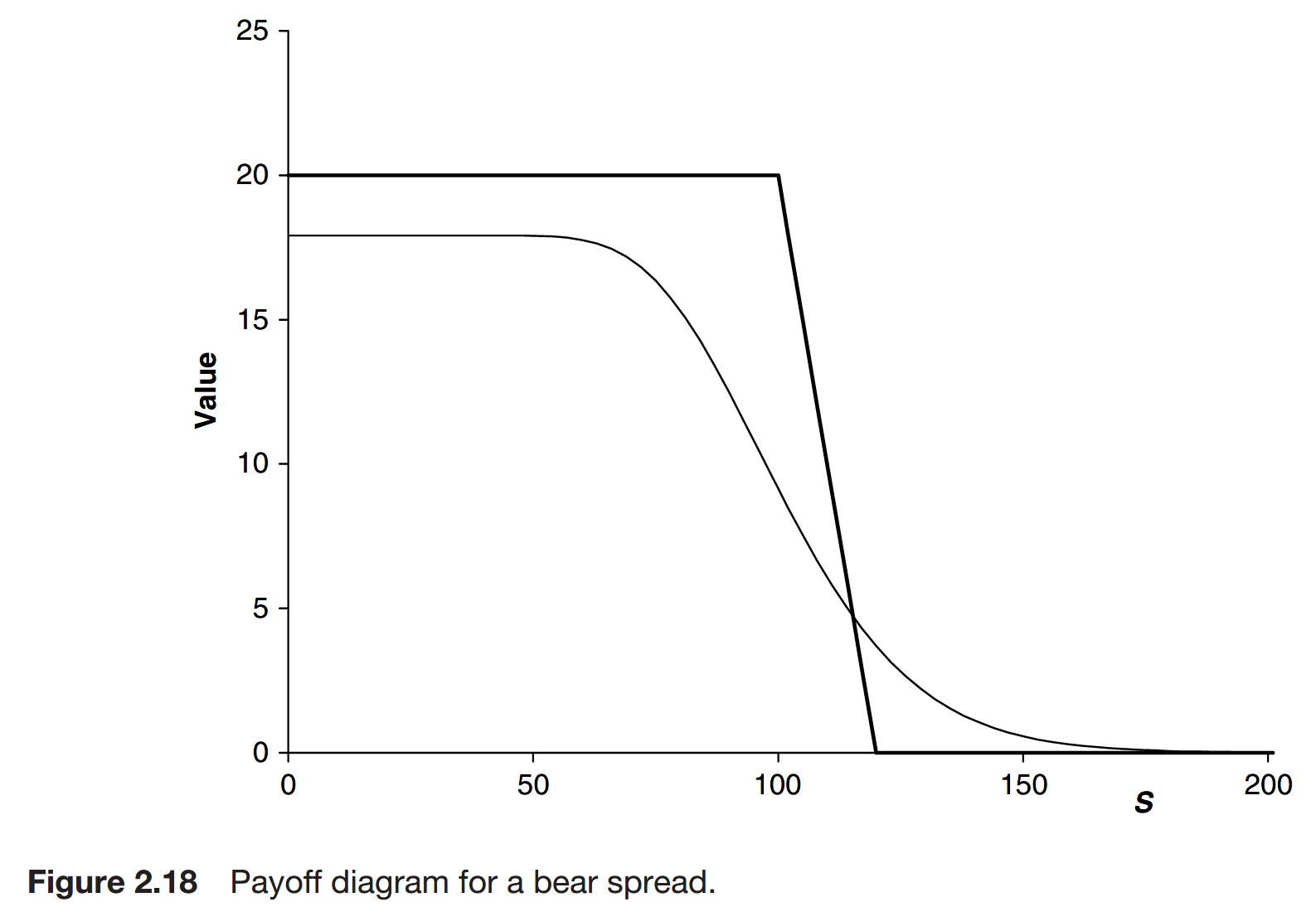

Bull and bear spread

The payoff for a general bull spread, made up of calls with strikes E1 and E2, is given by

where E2 > E1. Here I have bought/sold

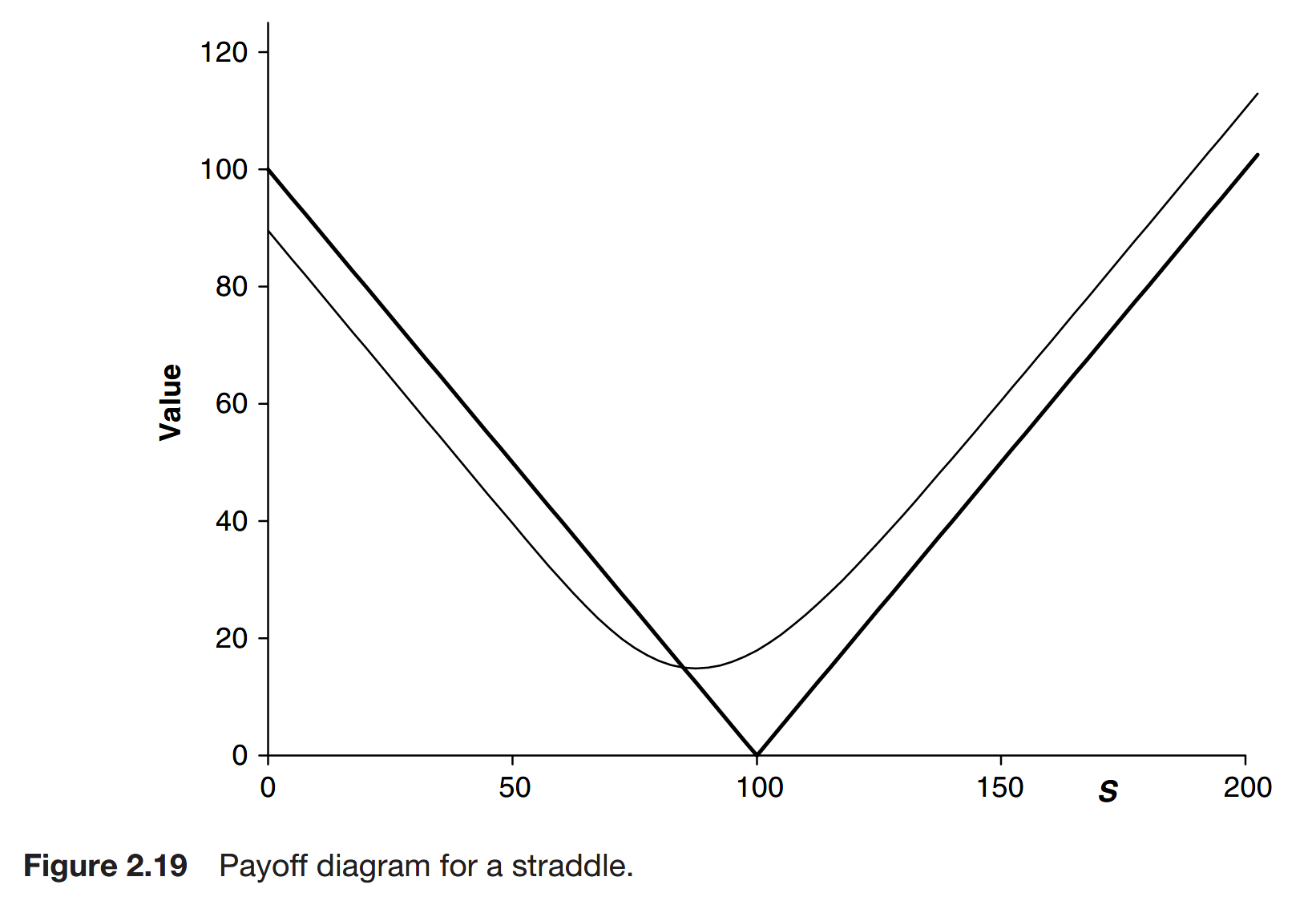

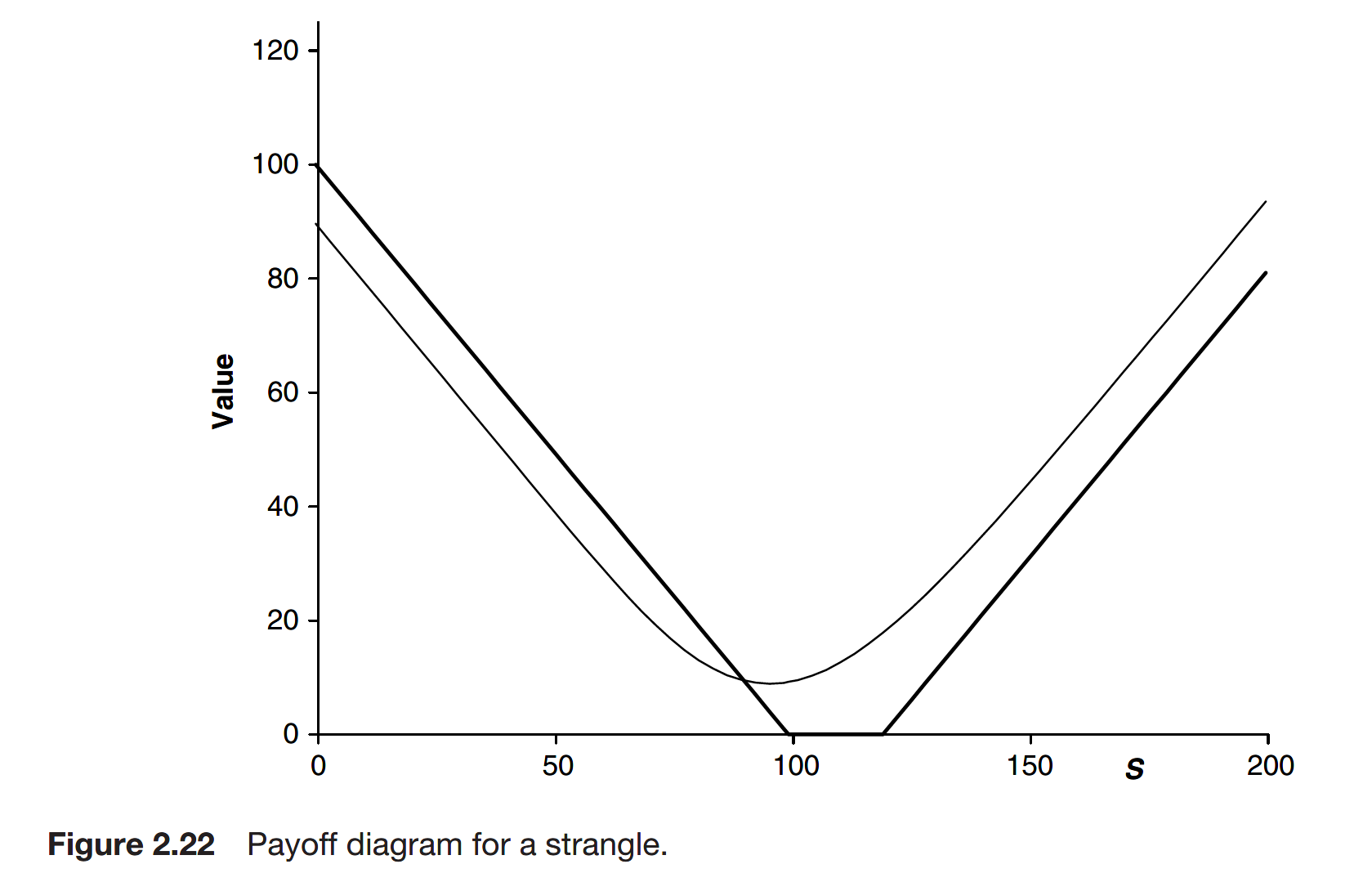

Straddles and strangles

The straddle consists of a call and a put with the same strike. Such a position is usually bought at the money by someone who expects the underlying to either rise or fall, but not to remain at the same level.

The strangle is similar to the straddle except that the strikes of the put and call are different. The contract can be either an out-of-the-money strangle or an in-the-money strangle. The motivation behind the purchase of this position is similar to that for the purchase of a straddle. The difference is that the buyer expects an even larger move in the underlying one way or the other. The contract is usually bought when the asset is around the middle of the two strikes and is cheaper than a straddle. This cheapness means that the gearing for the out-of-the-money strangle is higher than that for the straddle. The downside is that there is a much greater range over which the strangle has no payoff at expiry; for the straddle there is only the one point at which there is no payoff.

There is another reason for a straddle or strangle trade that does not involve a view on the direction of the underlying. These contracts are bought or sold by those with a view on the direction of volatility, they are one of the simplest volatility trades.

Straddles and strangles are rarely held until expiry.

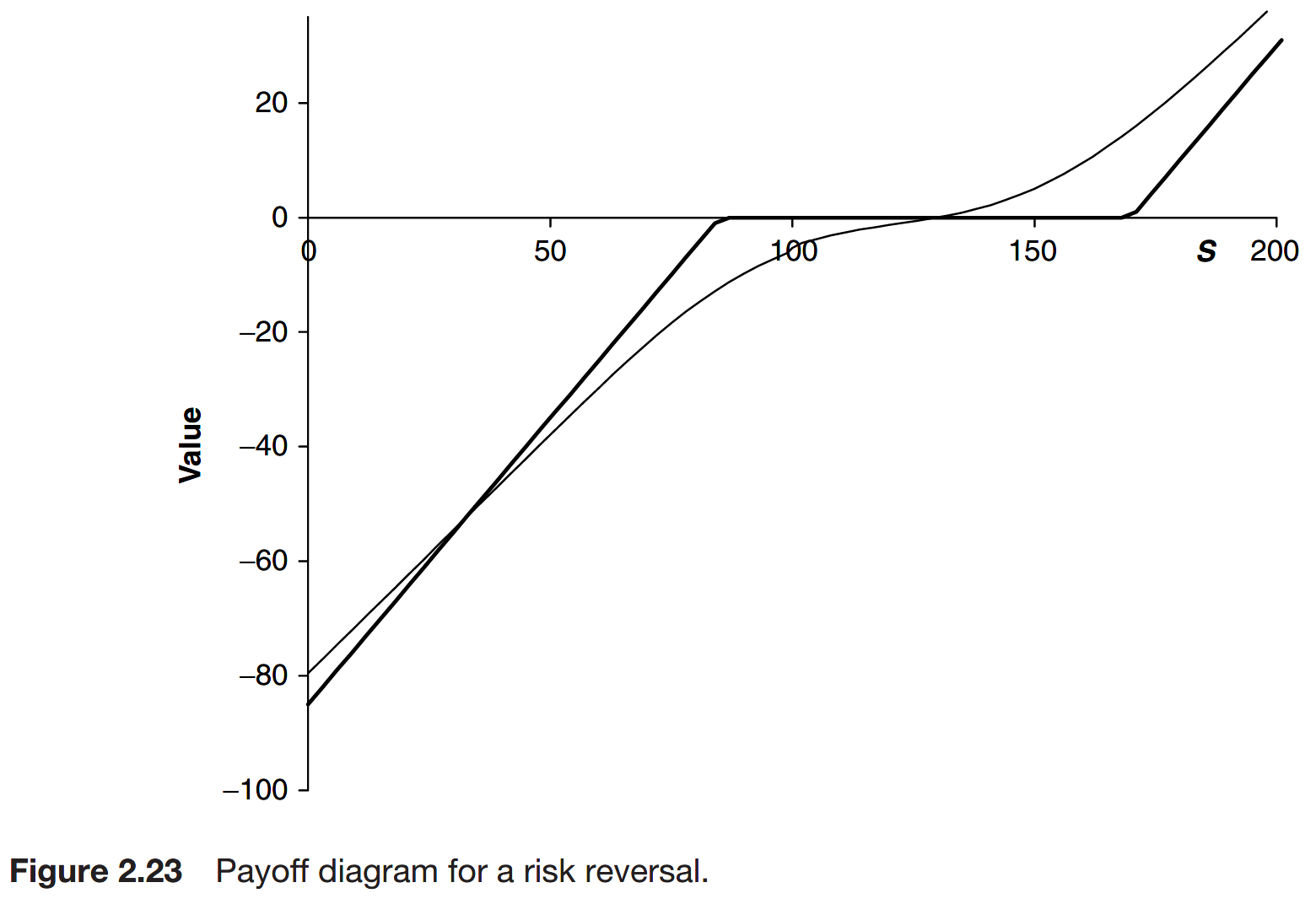

Risk reversal

The risk reversal is a combination of a long call, with strike above the current spot, and a short put with a strike below the current spot. Both have the same expiry.

The risk reversal is a very special contract, popular with practitioners. Its value is usually quite small and related to the market’s expectations of the behavior of volatility.

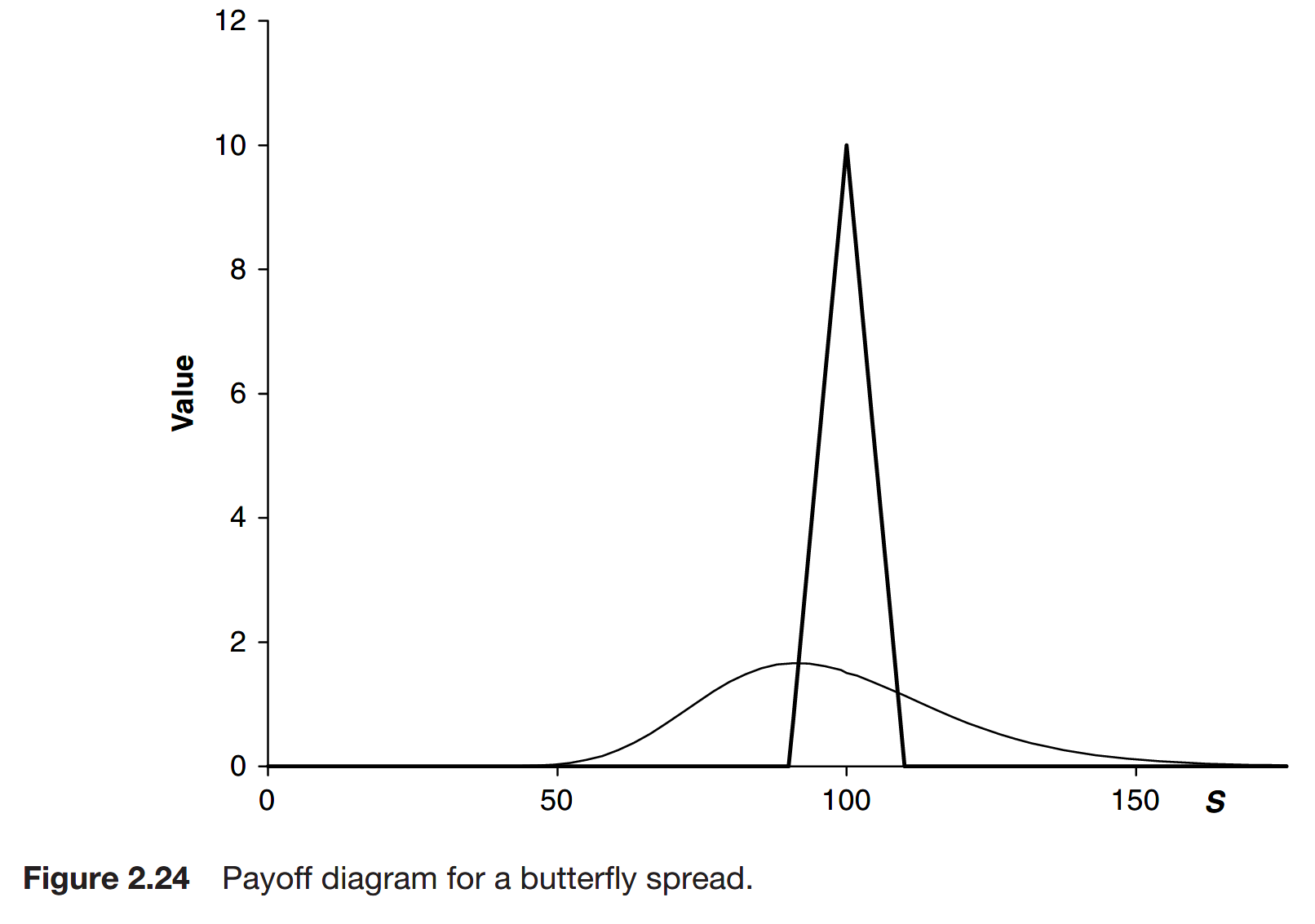

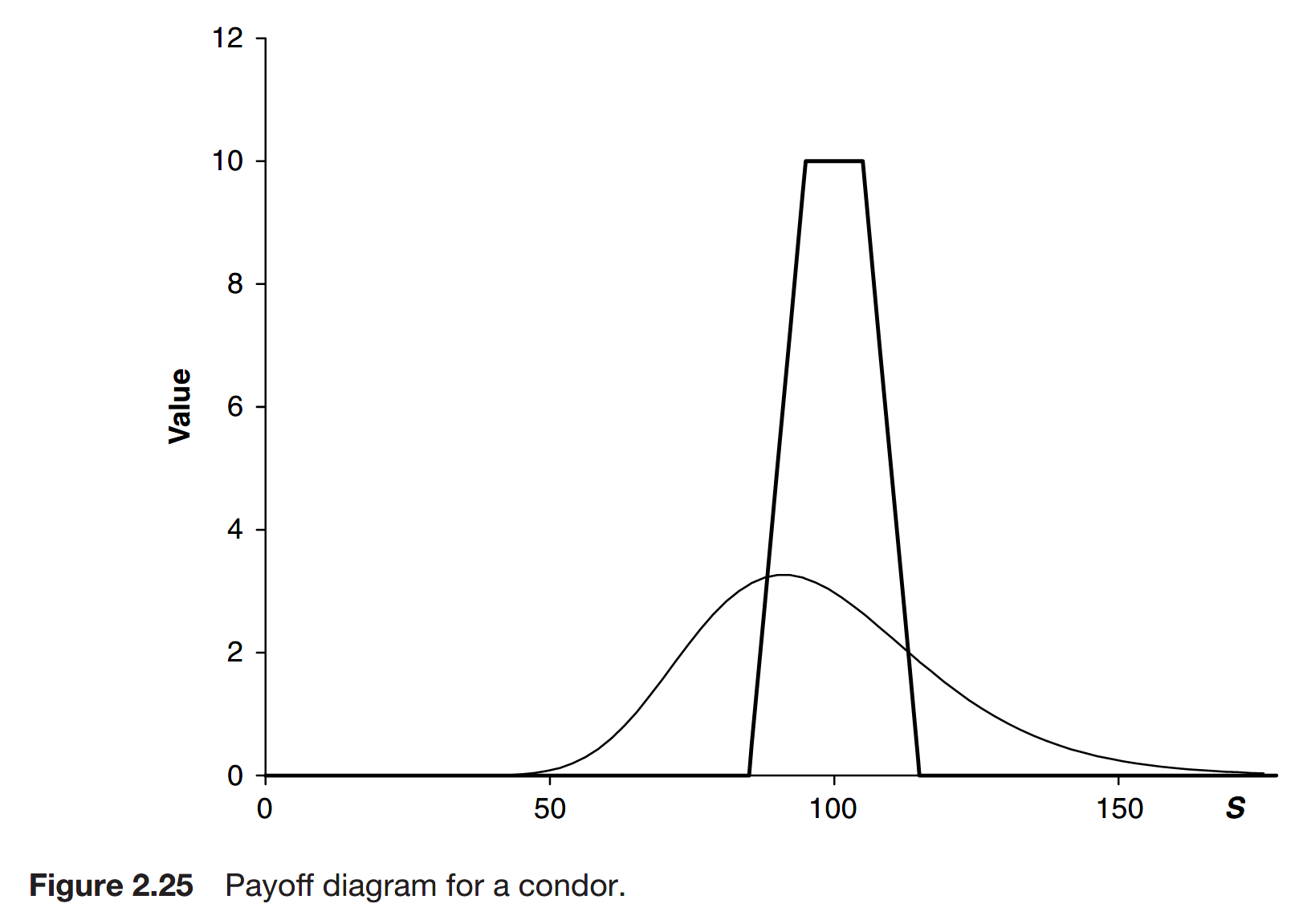

Butterflies and condors

A more complicated strategy involving the purchase and sale of options with three different strikes is a butterfly spread. This is the kind of position you might enter if you believe that the asset is not going anywhere, either up or down. Because it has no large upside potential the position will be relatively cheap.

The condor is like a butterfly except that four strikes, and four call options are used.

Calendar spreads

A strategy involving options with different expiry dates is called a calendar spread. You may enter into such a position if you have a precise view on the timing of a market move as well as the direction of the move. As always the motive behind such a strategy is to reduce the payoff at asset values and times which you believe are irrelevant, while increasing the payoff where you think it will matter. Any reduction in payoff will reduce the overall value of the option position.

leveraging decaying of time value between different expiration options with same underlying asset and same exercise price

Leaps and flex

LEAPS (Long-term equity anticipation securities) are longer-dated exchange-traded calls and puts.

- standardized

- available with expiries up to three years

- They come with three strikes, corresponding to at the money and approximately 20% in and out of the money with respect to the underlying asset price when issued.

In 1993 the CBOE created FLEX (FLexible EXchange-traded options) on several indices. These allow a degree of customization, in the expiry date (up to five years), the strike price and the exercise style.

Warrants

Warrants are call options issued by a company on its own equity. The main differences between traded options and warrants are the timescales involved, warrants usually have a longer lifespan, and on exercise the company issues new stock to the warrant holder. Exercise is usually allowed any time before expiry, but after an initial waiting period.

The typical lifespan of a warrant is five or more years. Occasionally, perpetual warrants are issued; these have no maturity.

Convertible bonds

Convertible bonds (CBs) have features of both bonds and warrants. They pay a stream of coupons with a final repayment of principal at maturity, but they can be converted into the underlying stock before expiry. This makes CBs similar to American options; early exercise and conversion are mathematically the same.

There are other interesting features of convertible bonds, callback, resetting, etc.

Over the counter options

A term sheet specifies the precise details of an OTC contract.

Further reading